Integrating Information Literacy in First-Year Writing

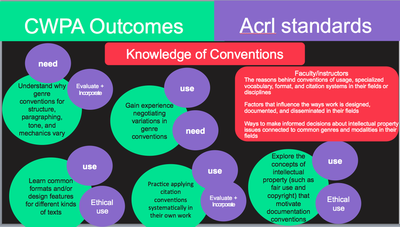

Information Literacy (IL) Librarians as well as writing scholars have frequently crossed disciplinary boundaries to explore the benefits of integrating IL into the teaching of writing and rhetoric (see Norgaard 2003, 2004; Jacobs and Jacobs 2009; Artman, Frisicaro-Pawlowski, and Monge 2010; Monge and Frisicaro- Pawlowski 2014). I have partnered with Angela Lucero, an IL Librarian at the University of Texas at El Paso, and we align ourselves with the creators of the Learning Information Literacy Across the Curriculum (LILAC) Project who have identified the extent to which the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Framework for Information Literacy in Higher Education coincides with the CWPA Outcome Statements. To further these conversations and develop action strategies for further interdisciplinary collaboration, we examine the collaborative experience and the products borne of a writing instructor and an instruction librarian’s decision to join forces and co-teach key portions of a course to enhance students’ acquisition of research and writing skills.

Once we began working together and incorporating IL in the FYW classroom we—like the aforementioned scholars did before us—found a significant overlap in our objectives. Together we shared the question posed by Jacobs and Jacobs (2009): “what might a focus on research as a process contribute to the teaching of Information Literacy in English composition courses?” Answering this question was itself a process—an organic experience where we realized that working together in increasing familiarity enhanced our respective methods of teaching the process of research in writing courses.

Having recognized the inefficiency of the “one-shot” library session for our purposes, we focus instead on how we exposed students to a co-created curriculum that approaches research from both a rhetorical and information literacy perspective, deploying this collaborative instruction at points in the course and their research process where these concepts and skills are crucial.

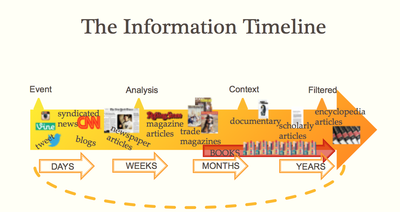

We begin with “rhetorical reading,” a series of discussions of scholarship as a conversation, and activities that orient students to the act of situating themselves in the rhetorical landscape of an issue. Next we “flip the library,” by which very basic library instruction is bypassed through the use of video tutorials and worksheets completed outside of the classroom in favor of practicing practical, strategic search methods in the context of their own areas of investigation. Then, students turn their “questions into queries.” This is a session of guided inquiry in which students consider their own focal topics to create a guide in class that fosters a process trial and error while searching for information. This enables students to effectively translate their own questions into searchable queries for use and manipulation in multiple search tools. Additionally we have a guided discussion with illustrative activities, the “information timeline,” about the different forms information can take, and which types of questions can be answered by a source based on its temporal relation to a subject or an event. Students then engage with the “CRAAP test,” in which guidelines are presented to students for critically evaluating a source for quality, reliability, and subjectivity to be applied to sources they have gathered thus far. The research portion of the semester is rounded out with an organic consultation-style class session in which both writing instructor and librarian spot-check students’ progress to jointly identify better ways to “incorporate research” into their papers.

Through our collaboration, we have refined our method of teaching the research process over time with attention to student output, formative assessment measures, anecdotal feedback, and the growth we have experienced in our respective fields. The progress we experienced in partnership makes it clear to us that writing instructors’ and librarians’ collaborative efforts in the classroom is a relationship worth expanding and sustaining. We continue these innovations with attention to our students to empower them to become “rhetorical researchers” by obtaining and using information deftly—skills of lasting utility not only in rhetoric and composition classes, but also throughout their university coursework, into their roles as professionals, and throughout a lifetime of critical and engaged citizenship.

Our collaboration was showcased at the 2016 Conference on College Composition and Communication, and we, along with other faculty librarian teams from other institutions, have proposed a workshop presentation at the 2017 Conference on College Composition and Communication.

-Co-written with Angela Lucero

-First and third photos created by Angela Lucero for the "Flipping the Library" presentation at the Conference on College Composition and Communication 2016.

Once we began working together and incorporating IL in the FYW classroom we—like the aforementioned scholars did before us—found a significant overlap in our objectives. Together we shared the question posed by Jacobs and Jacobs (2009): “what might a focus on research as a process contribute to the teaching of Information Literacy in English composition courses?” Answering this question was itself a process—an organic experience where we realized that working together in increasing familiarity enhanced our respective methods of teaching the process of research in writing courses.

Having recognized the inefficiency of the “one-shot” library session for our purposes, we focus instead on how we exposed students to a co-created curriculum that approaches research from both a rhetorical and information literacy perspective, deploying this collaborative instruction at points in the course and their research process where these concepts and skills are crucial.

We begin with “rhetorical reading,” a series of discussions of scholarship as a conversation, and activities that orient students to the act of situating themselves in the rhetorical landscape of an issue. Next we “flip the library,” by which very basic library instruction is bypassed through the use of video tutorials and worksheets completed outside of the classroom in favor of practicing practical, strategic search methods in the context of their own areas of investigation. Then, students turn their “questions into queries.” This is a session of guided inquiry in which students consider their own focal topics to create a guide in class that fosters a process trial and error while searching for information. This enables students to effectively translate their own questions into searchable queries for use and manipulation in multiple search tools. Additionally we have a guided discussion with illustrative activities, the “information timeline,” about the different forms information can take, and which types of questions can be answered by a source based on its temporal relation to a subject or an event. Students then engage with the “CRAAP test,” in which guidelines are presented to students for critically evaluating a source for quality, reliability, and subjectivity to be applied to sources they have gathered thus far. The research portion of the semester is rounded out with an organic consultation-style class session in which both writing instructor and librarian spot-check students’ progress to jointly identify better ways to “incorporate research” into their papers.

Through our collaboration, we have refined our method of teaching the research process over time with attention to student output, formative assessment measures, anecdotal feedback, and the growth we have experienced in our respective fields. The progress we experienced in partnership makes it clear to us that writing instructors’ and librarians’ collaborative efforts in the classroom is a relationship worth expanding and sustaining. We continue these innovations with attention to our students to empower them to become “rhetorical researchers” by obtaining and using information deftly—skills of lasting utility not only in rhetoric and composition classes, but also throughout their university coursework, into their roles as professionals, and throughout a lifetime of critical and engaged citizenship.

Our collaboration was showcased at the 2016 Conference on College Composition and Communication, and we, along with other faculty librarian teams from other institutions, have proposed a workshop presentation at the 2017 Conference on College Composition and Communication.

-Co-written with Angela Lucero

-First and third photos created by Angela Lucero for the "Flipping the Library" presentation at the Conference on College Composition and Communication 2016.